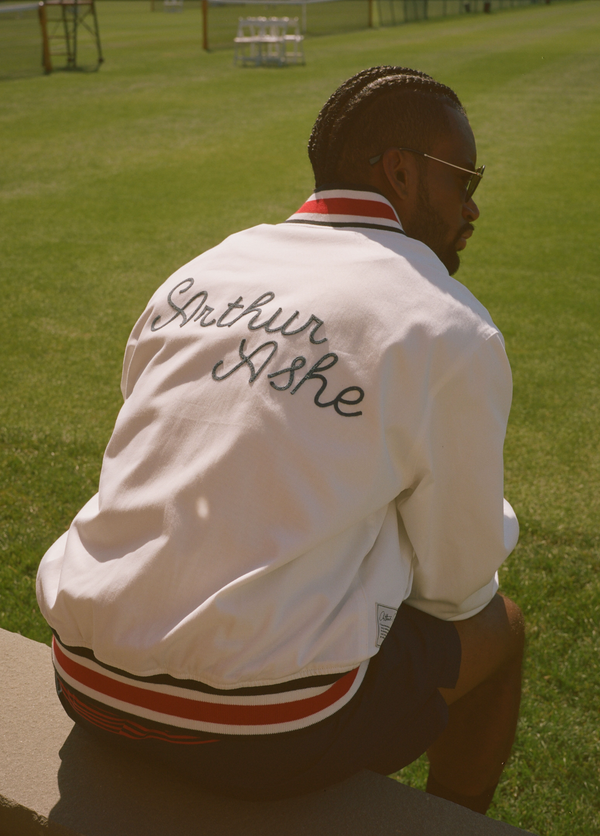

Summer '24 Collection

Arthur Ashe: Icon. Activist. Champion.

Arthur Ashe was a legendary tennis player: he was the first Black man to win the U.S. Open, Wimbledon, and a slate of other history-making titles. But he was also a champion for civil rights and social justice; an activist for numerous initiatives related to heart health, urban health, and HIV/AIDS; an advocate for youth access to sports; a style icon; a paragon of sportsmanship; and an American hero.

An Early Start

(1943-1960)

Born in Richmond, Virginia, Ashe began playing tennis at a segregated municipal park where his father was caretaker. (Too skinny for football, Ashe spent his early years practicing his serve on the courts outside the small cottage on the park grounds where his family lived.) By age seven, he was already turning heads, and a local trainer, Ron Charity, brought Ashe to the attention of Robert Walter Johnson. Dr. Johnson, a leader in the burgeoning African-American tennis community, took Ashe under his wing, always stressing the importance of sportsmanship, etiquette, humility and composure: characteristics that would come to define Ashe’s career and legacy.

Rising Through Adversity

(1960-1963)

Ashe’s tennis skills were developing rapidly, but in Richmond he was barred from competing against white students and from using the city’s indoor courts. So Ashe accepted an invitation to spend his senior year of high school with a friend of Dr. Johnson’s in St. Louis. There, he was able to train on the National Guard’s indoor courts, and, after some successful lobbying by Dr. Johnson, participate in the previously-segregated U.S. Interscholastic Championships and the National Junior Indoor Championships — winning both.

UCLA and the Davis Cup

(1963-1968)

In 1963, Ashe was awarded a tennis scholarship to UCLA, where he won both the NCAA singles and doubles titles. While he was a student, he was named to his first U.S. Davis Cup team — becoming the first Black player ever selected, and beginning a long relationship with the historic tournament: he would go on to help the U.S. win four Davis Cup tournaments and wore his U.S. team jackets with pride throughout his life, later serving as captain. Upon graduation from UCLA, Ashe was commissioned in the army and assigned to the United States Military Academy at West Point to serve as a data processor and the academy’s tennis coach.

Making History at the U.S. Open

(1968)

In a history-making upset, Ashe won the 1968 U.S. Open against Tom Okker of the Netherlands 14–12, 5–7, 6–3, 3–6, 6–3. In doing so, Ashe became both the first Black man and the only amateur ever to win the title — and the first American to win in over a decade. In order to maintain Davis Cup eligibility and have time away from his army duty to compete, Ashe was required to maintain amateur status; but this also meant he could not accept the $14,000 prize, which was given to Okker instead.

A Legend in the Making

(1968-1973)

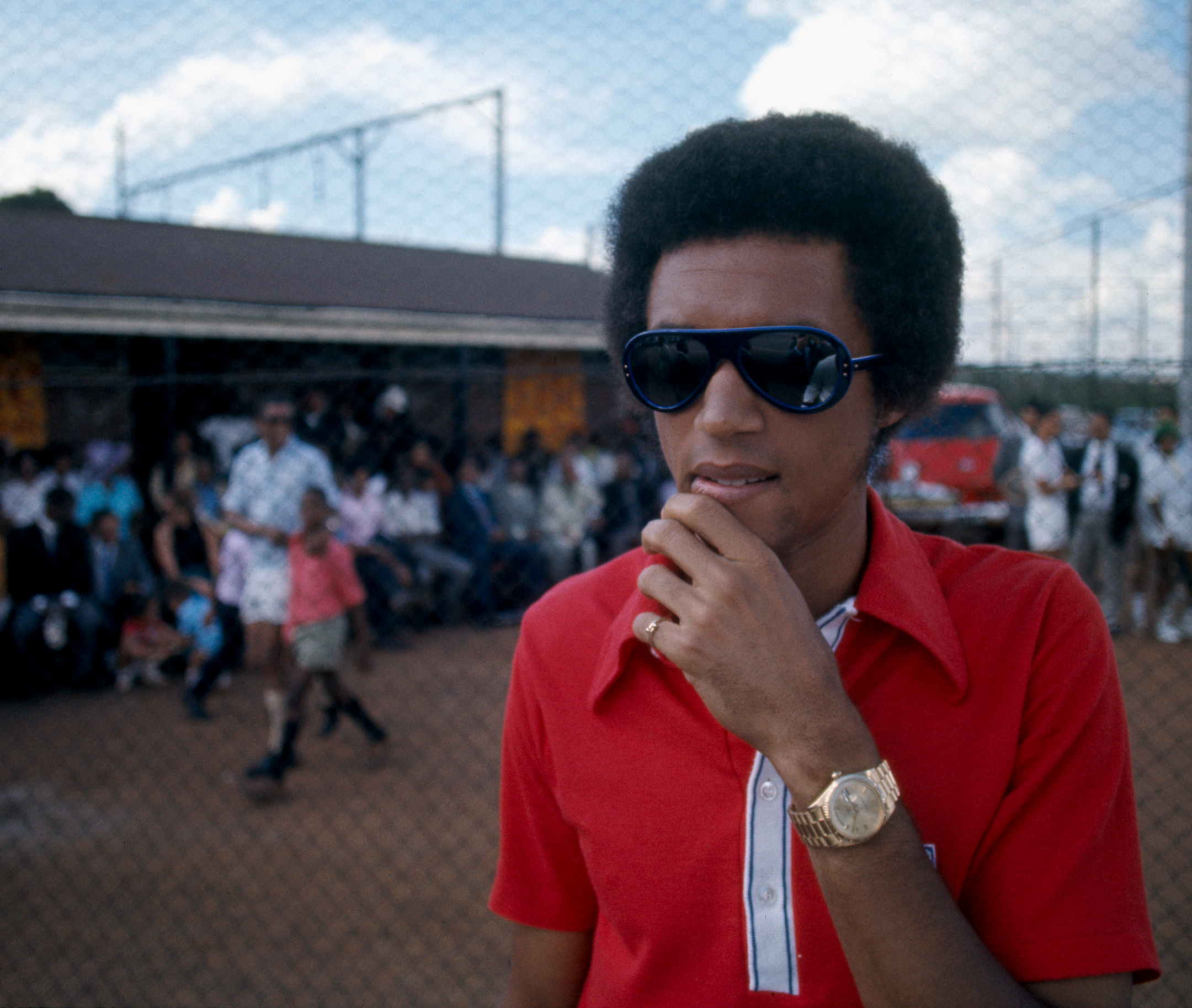

Ashe continued his dominant form on the court, and began to wade in earnest into matters of social justice. Helping the U.S. to victory with dominant performances in the 1968, 1969, and 1970 Davis Cup tournaments, Ashe also won his second Grand Slam singles title at the Australian Open in 1970, where he became the first Black man to win the title and the first non-Australian to win in over a decade. He conquered the French Open men’s doubles the following year, all while embroiled in a years-long battle with the apartheid-era South African government, having been repeatedly denied a visa to play in the country.

Breaking Barriers

(1973-1975)

In 1973, Ashe was finally granted a visa to play in South Africa, and saw it as an opportunity to break down stereotypes and highlight ongoing racial discrimination around the world while celebrating the potential of a fully integrated society. Competing in the men’s doubles with his former rival Tom Okker as his teammate, Ashe won the 1973 South African Open — breaking the color barrier in South Africa a full twenty years before the fall of apartheid. Ashe also funded and dedicated the building of a tennis center for Black South Africans in Johannesburg’s Soweto township.

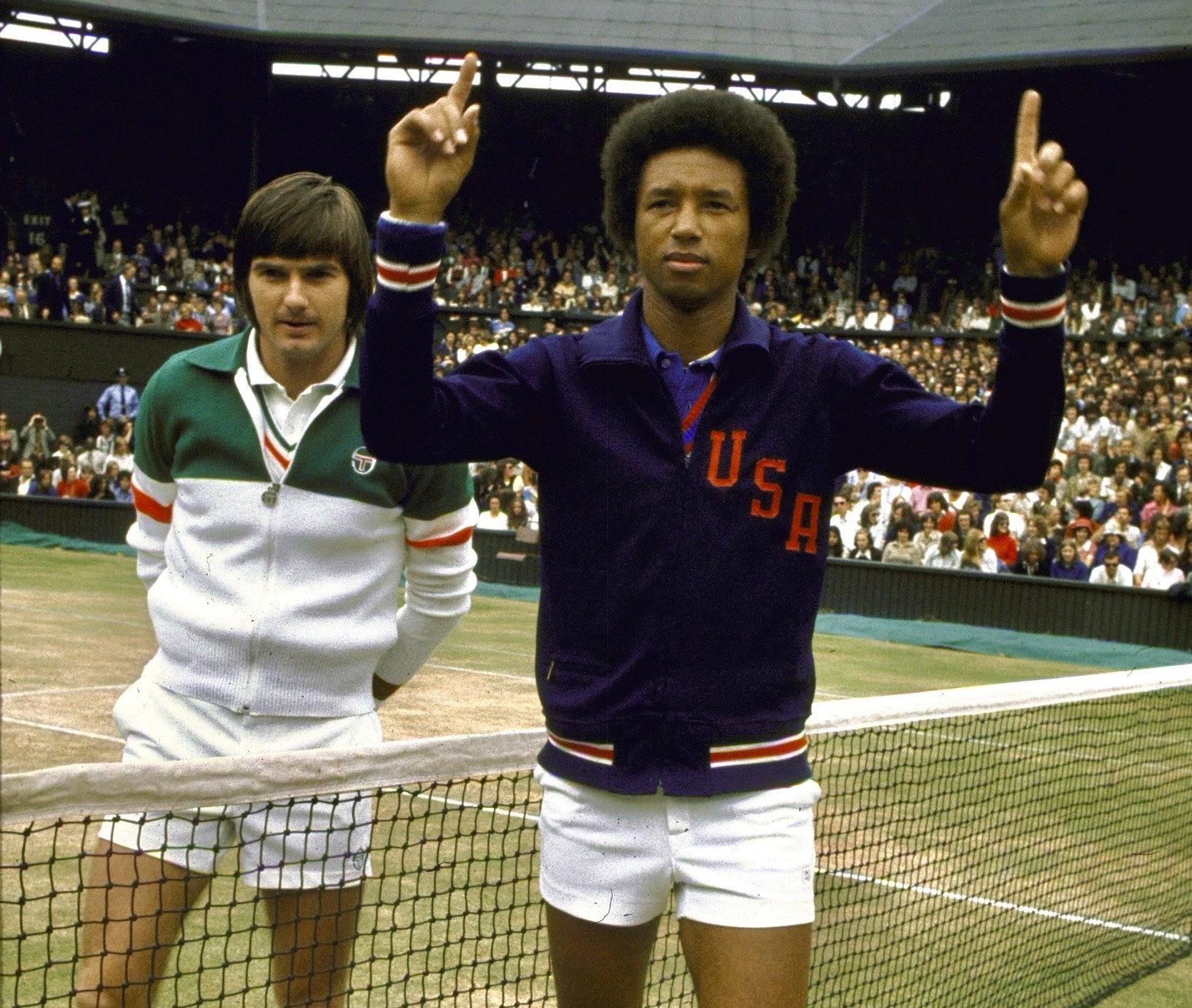

Winning Wimbledon

(1975)

In 1975, fresh off of beating Björn Borg in the WCT Finals, Ashe upset his rival and defending champion Jimmy Connors to win Wimbledon, becoming, as with many of his titles, the first Black man to do so. Ashe had never beaten Connors in any previous match, and Connors had not lost a single set during the entire tournament until the final. Ashe’s tactical game and four-set victory has been called “near perfect.” Prior to the match, Ashe and Connors had a long-standing dispute related to Connors’ non-participation on the U.S. Davis Cup team, and Ashe symbolically wore his iconic U.S.A. warm-up jacket during the Wimbledon prize ceremony.

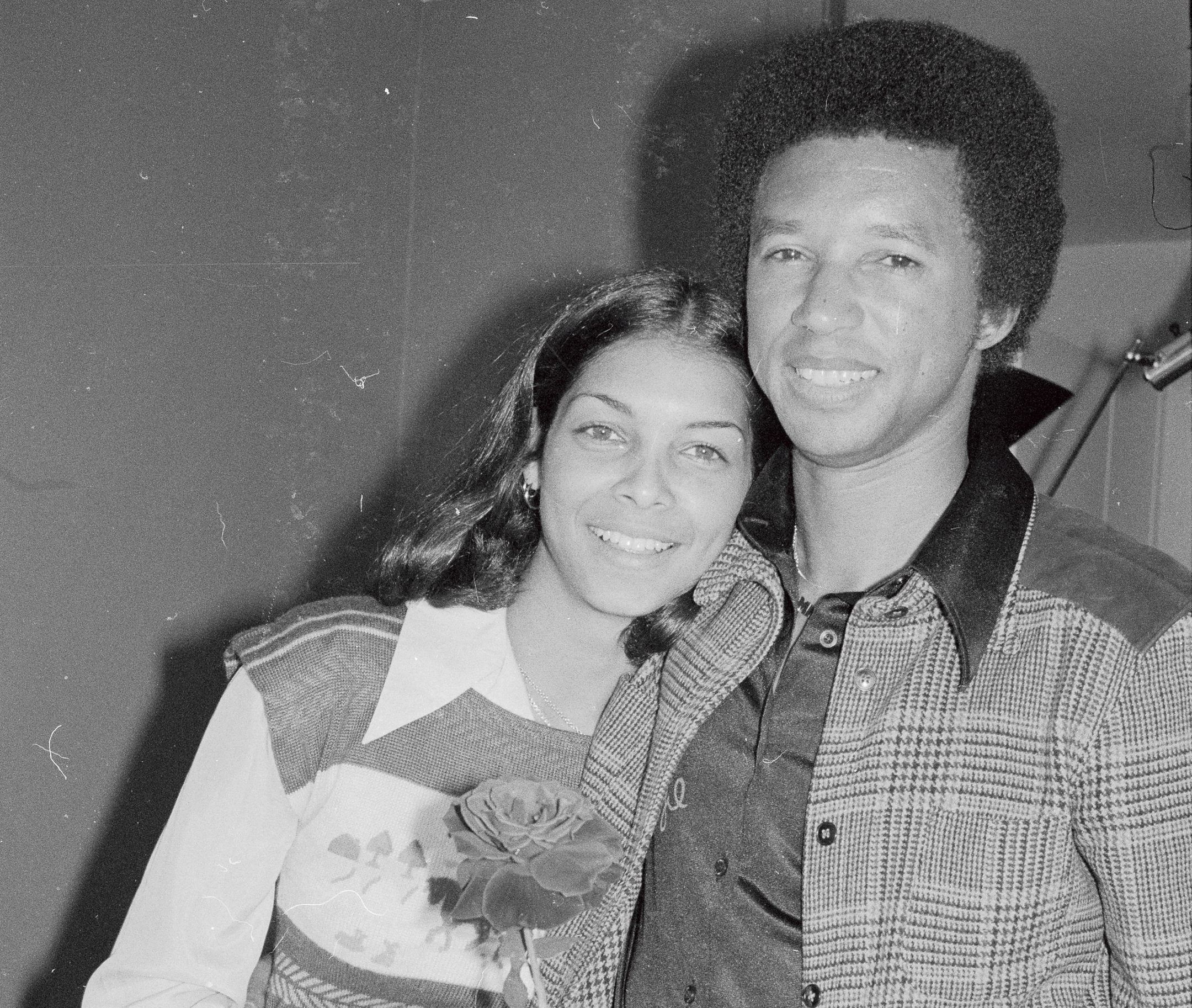

A New Chapter

(1976-1980)

In 1976, Ashe met photographer and graphic artist Jeanne Moutoussamy, and the two were married the following year at the Church Center for the United Nations in New York City. In 1979, at the age of 36, Ashe suffered a heart attack while holding a tennis clinic in New York and underwent a quadruple-bypass surgery. As a relatively young man and one of the world’s top athletes, Ashe used his experience to draw attention to the hereditary aspect of heart disease and became national campaign chairman for the American Heart Association. In 1980, at the age of 36, Ashe officially retired from the game he’d helped revolutionize.

A Captain, a Family Man, an Activist

(1980-1986)

Unmoored from professional tennis’s grueling scheduleaside from being named captain of the U.S. Davis Cup team in 1981), Ashe had more time to focus on matters of health and social justice, as well as his own family. Ashe served in a delegation of 31 prominent African-Americans selected to observe South Africa’s transition to racial integration. He and Jeanne adopted their daughter Camera (named for Jeanne’s profession) in 1986, shortly after Ashe had been arrested for participating in an anti-apartheid rally at the South African embassy. Ashe would be arrested again for protesting the U.S. government’s treatment of Haitian refugees outside the White House in 1992.

Days of Grace

(1988-1993)

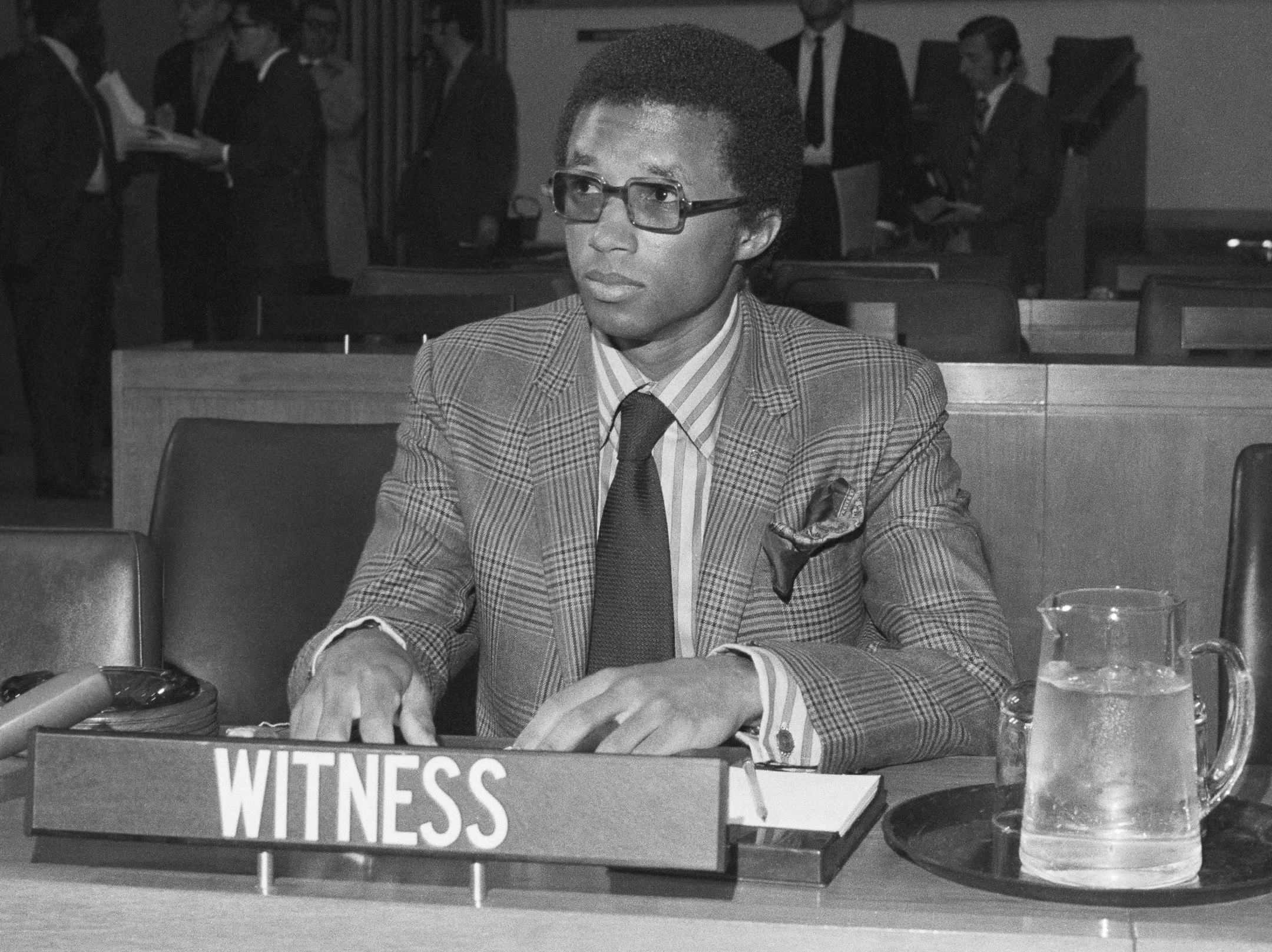

In 1988, Ashe published A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African-American Athlete; he considered the book to be among his most significant accomplishments. But the end of Ashe’s life was defined by an entirely different issue: on April 8th, 1992, he publicly revealed that he had contracted HIV, speaking frankly about the myriad misconceptions concerning HIV and AIDS. He managed to found the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health, finish his memoir Days of Grace, accept Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year award, and deliver a poignant address at the United Nations on World AIDS Day before his passing from AIDS-related pneumonia on February 6th, 1993, at the age of 49.

A Legacy Beyond Tennis

(1993-Today)

Ashe was posthumously awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom and named the Arthur Ashe Humanitarian of the Year by the ATP; the USTA National Tennis Center’s main stadium in Flushing, New York, was named after him; UCLA established both the Arthur Ashe Student Health and Wellness Center and the Arthur Ashe Legacy Fund; and an ESPY Award was created in his honor. Perhaps most notably, in a poignant reflection of his ability to transcend entrenched barriers across all scales, a statue of Ashe was raised in Richmond, Virginia, the former capital of the confederacy and Ashe’s hometown.

More than a tennis champion, Arthur Ashe was a humanitarian. We’re continuing his legacy.

A Towering Legacy

A legacy that transcends tennis. Learn more about Arthur Ashe’s life, both on and off the court.

A Fight For Change

Arthur Ashe fought for many important causes during his career. Learn more about his impact.